To be a female soccer fan in Iran who wants to see her team play in person requires two challenging steps — first, devising a creative strategy to enter the stadium, and then, breaking the law — thanks to a government ban that restricts Iranian women from attending male sporting events in stadiums. For Sara (a pseudonym to protect her identity), a 33-year-old teacher, women’s rights advocate, and sports fan who grew weary of watching games on television, that strategy involved joining three other women in an attempt to enter a World Cup qualifying soccer game between Iran and South Korea held in Tehran’s Azadi Stadium in 2009. The four women drove to the Korean Embassy and delivered a hand-written note to a group of Korean women on their way to watch the game. It read: “While you can go to our stadium, we (Iranian women) can’t. Please be our voice.”

Sara says they hoped the Korean women would sneak the four of them inside the stadium with their group. “It was so bizarre for them. None of them really understood the note. But an Iranian man who was working with the Korean embassy asked us, ‘Do you want to go to stadium?’” They told him they did. “He gave us tickets, and we drove behind the Korean spectators’ bus to the stadium and pretended to be a part of their group.” They entered the stadium, and Sara described what she saw as a surreal experience. “It was like you were watching something on the TV, and then suddenly you enter the scene and everything becomes 3D,” she says. But that excitement soon faded. During the game, she and her friends asked the Korean group to pose for pictures with the note they had written in Korean, English, and Persian. At this point, the manager for the Korean group, an Iranian woman, noticed Sara’s group and immediately handed them over to the security. “I thought ‘I will sleep in prison tonight,’” she says. “I was older than the other three girls so I felt responsible. It was nerve-racking, but surprisingly security only told us to sit separate from the Koreans and nothing else.”

Most female fans are not that fortunate. Women face grave repercussions for attempting to sneak into stadiums (either in disguise, or, as Sara did, with a ruse). Arrests and beatings are the standard punishment. For example, Ghoncheh Ghavami, a British-Iranian woman, was arrested in 2014 for trying to enter a FIVB Volleyball World League match between Iran and Italy at Azadi Stadium. She was protesting the new ban on women’s presence in volleyball matches, which was enacted in 2012. As punishment, she was kept in solitary confinement for 100 days and later placed on trial. She was sentenced to an additional year in jail and banned from traveling. Ghavani’s treatment and the trial created an international uproar. Amnesty International took notice and pressured the Iranian government to drop the charges. The Iranian government succumbed to the pressure and released her, but bans regarding female sports fan continued.

Sara says her enthusiasm for sports began when she was 13 years old, a time when her homeland enjoyed a series of soccer achievements. In 1996, Iran’s soccer team won third place in the Asian Cup and qualified for the 1998 World Cup. These victories amplified national interest and excitement as Iran, the once undefeated Asian champion and winner of three consecutive cups in 1968, 1972, and 1976, returned to winning after a victory drought of almost 20 years. That drought was prompted by political instability. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War played key roles in the decline in sports interest and achievement. The revolution also produced the sports ban on women, which prohibited them from attending and watching games played by men. In the late 1990s, as men rejoiced in the revival of Iran’s soccer team and reveled in the country’s most beloved sport, the women failed to notice their exclusion from games. Other restrictions imposed by the revolution, such as the mandatory hijab, impacted their lives in more profound ways.

Ironically, “azadi” means “freedom” in Persian, Iran’s official language.

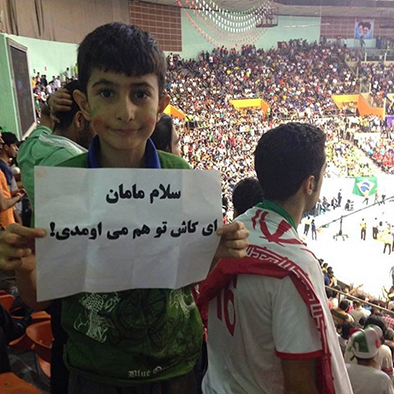

But in 2005, almost 25 years after the ban, Sara and a group of almost two dozen women decided to push back on the sports ban and protested in front of Azadi Stadium, the venue for most of the major sporting events. (Ironically, “azadi” means “freedom” in Persian, Iran’s official language). That was the birth of the @OpenStadiums campaign. It’s also referred to as the White Scarves campaign because in the third and final protest, the women used hijabs of white scarves upon which they wrote their campaign’s slogan: “My share, half of the azadi.” They used hijabs instead of posters for their slogan because police could tear away the placards, but wouldn’t remove their mandatory hijabs. Sara says that after demonstrating publicly in front of Azadi Stadium three times from 2005 to 2008, members of the group decided to conceal their identities because authorities began to physically assault and beat protesters. They sought to avoid arrest and shifted to social media to actively advocate for their cause and to attract the attention of the international sports community.

But even social media use comes with risk and requires vigilance. The government actively monitors it — especially after 2009, when Iranians took to Twitter to protest the presidential election, which became known as the Persian Awakening and prompted a crackdown on all social media, including civil movements like @OpenStadiums. However, a visit to Iran by former FIFA President Sepp Blatter and the election of Hassan Rouhani as president of Iran encouraged @OpenStadiums to resurface on social media through Facebook and Twitter. Blatter took notice of the movement and wrote a letter to the Iranian government on Women’s Day in 2013, asking to lift the ban. Even though Rouhani’s government implemented new bans on women, such as the 2014 ban on women attending volleyball matches, social-media monitoring lessened.

Although, @OpenStadiums still operates anonymously and the ban remains, Sara sees progress. “Our most important achievement is that we made people, and women in particular, sensitive about this discrimination. Eleven years ago, even some women’s rights activists made fun of us and did not take us seriously. But we said this is symbol of excluding women from society,” she says. “Many people thought watching football in stadiums was something cheap or low-level so they did not care. But, now, things are completely different. If you check any news or comments about women’s absence from stadiums, most people are reacting and showing their disagreement against this discrimination.”