Think of kushti, a traditional sport of Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, as a combination of the strategy and smarts of karate and the down-and-dirty theater of mud wrestling. Royal families of the region patronized the sport in the 1600s, but it remains a popular game of speed, strength, and stamina. A match (called a dangal) lasts 15 minutes to an hour or more (as compared to a typical Western wrestling match that includes three, three-minute periods).

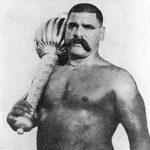

Qaiser Khan, 37, a professional pehlwan (wrestler) from Lahore, Pakistan who earned the title of Sher-e-Lahore (Lion of Lahore), began playing the sport at 11 years old with the urging of his father. He was sent to live under the patronage of a guru (mentor). Pehlwans follow a strict routine of exercise and diet overseen by coaches and mentors. “We were woken up at the crack of the dawn to exercise for hours,” he says. “I dreaded that time.” The exercises included dand (pushups), bethak (squats), and dura (a combination of pushups and situps). After doing some exercises at home, they would go to akhara (the local gymnasium featuring a mud pit) to practice. By the time they returned, they would have completed nearly 3,000 dand, bethak, and duras. Wrestlers would consume sardai, a drink made of almonds, milk, and herbs following the intense workout. A pehlwan’s diet also includes meat, ghee (clarified butter), and flatbread.

In the afternoon, they prepared for another workout round, which began by going to the akhara and digging up the mud pit with the hoe. Then, pehlwans would plough the akahara to make the ground leveled and soft. However, instead of using an animal to prepare the area, one of the pehlwans would be harnessed to the plow and a few people would ride on it to increase the difficulty. After the akhara was ready, they would begin to practice the game, which would continue until 7 p.m.

On competition day, fans place huge bets on wrestlers. Pehlwans arrive at the pit amid the cheering crowd and traditional drum (dhol) beat wearing their loin cloths. The mud is often mixed with oil, or ghee, and ochre that imparts a red hue. It is prepared carefully with a routine sprinkling of water so that the floor is not hard enough to cause injury, but not soft enough to impede movement. The game is simple, yet challenging — pin your opponent to the ground. There are three primary moves daw (moves), pech (countermoves), and pantra (stance). During the game, each player tries to put the opponent on their back, and whenever a player succeeds, the referee taps the player to let him know that he has won the game. There are no points, penalties, rounds, or timeouts.

Despite its history, kushti is dying in Lahore, the second-largest metropolitan area in Pakistan and a city that was once filled with akharas. Now, there are only a few left. At one time, famous pehlwans were treated as celebrities and their posters were displayed across the city before a competition. “There is only respect and fame, but not a financial future for a pehlwan,” Khan says. “It was a symbol of Pakistan and India, but it is not supported anymore by the Pakistani government.”